Final Report

Parallelizing Pauli Paths (P3): GPU-Accelerated Quantum Circuit Simulation

Summary

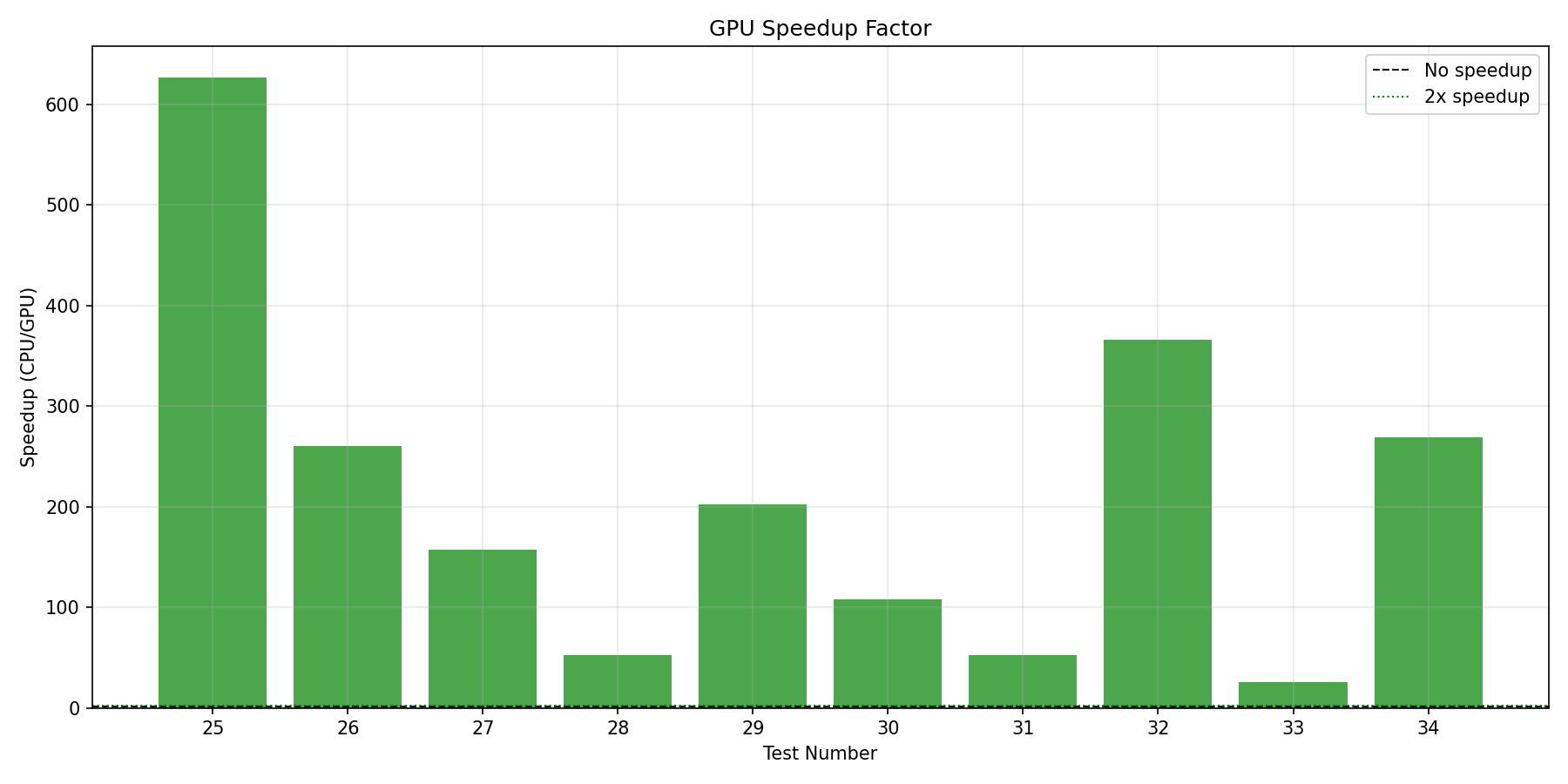

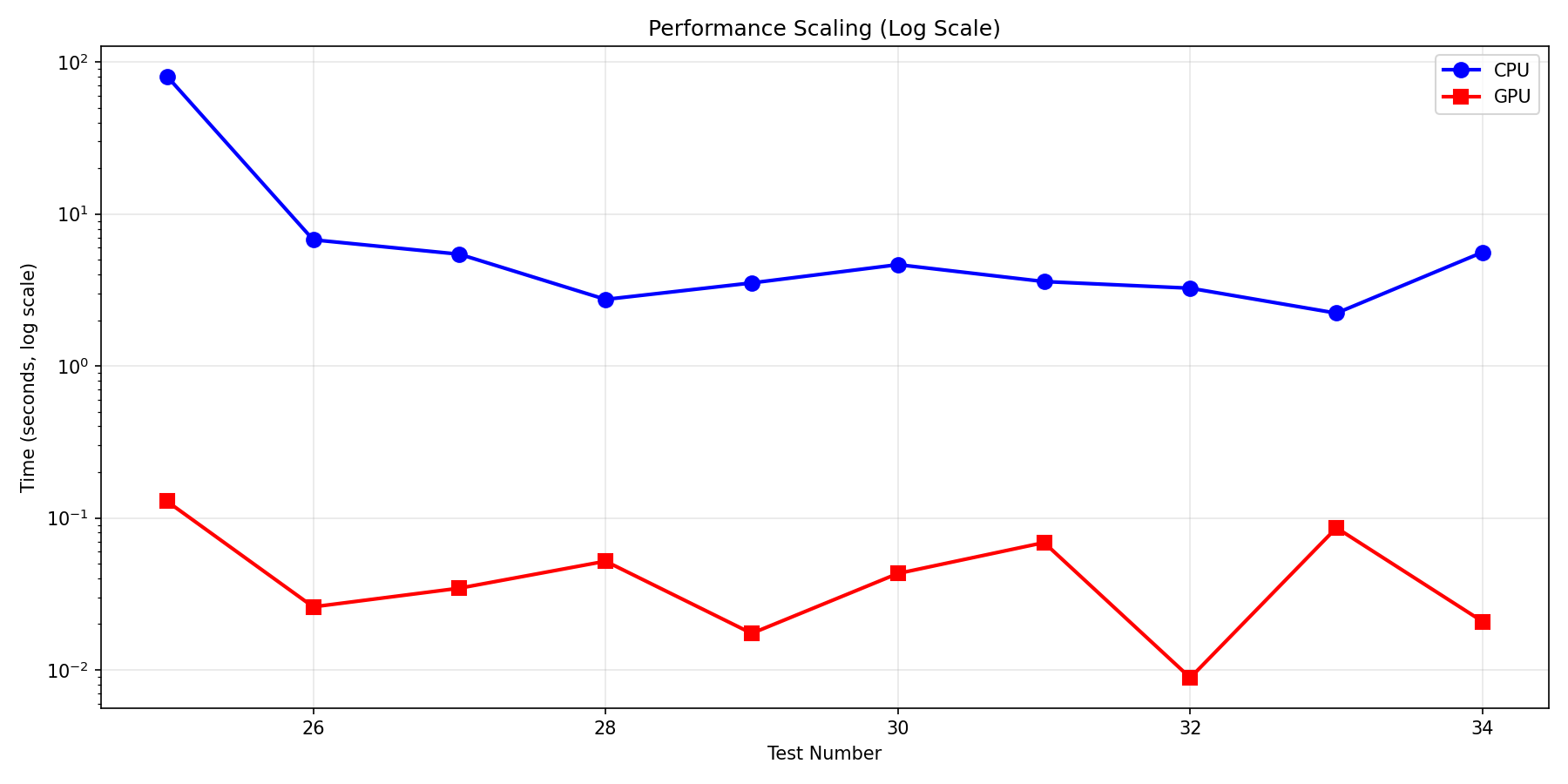

We implemented a GPU-accelerated Pauli path propagation algorithm for quantum circuit simulation using CUDA on NVIDIA GPUs and compared it against a single-threaded CPU baseline in C++. Our CUDA implementation on the GHC cluster machines (NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 GPUs) achieves speedups of up to 626× on large-scale simulations, with an average speedup of 213× across our stress test suite containing circuits with 500–30,000 initial Pauli words and 50–500 layers.

Project deliverables include:

- Fully functional CPU simulator (

pauli.cpp, ~436 lines) serving as single-threaded baseline - GPU simulator using CUDA (

pauli_gpu.cuwith device operations ingates.cu_inl) - Comprehensive test suite with 34+ test cases validating numerical correctness

- Performance benchmarks comparing CPU vs GPU across various circuit configurations

- Python visualization tools demonstrating Pauli word dynamics and performance characteristics

All implementations run on GHC cluster machines with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 GPUs.

Background

Motivation

In quantum computing, a central computational task is estimating expectation values of observables. Given a quantum circuit \( U \) that prepares a state \( \lvert \psi \rangle = U \lvert 0 \rangle \), we seek to compute \( \langle \hat{H} \rangle = \langle \psi \lvert \hat{H} \lvert \psi \rangle \) where \( \hat{H} \) is the observable of interest, typically decomposed as a sum of Pauli words. This expectation value is fundamental in quantum algorithms such as variational quantum eigensolvers for quantum chemistry and quantum approximate optimization algorithms.

Classical simulation of quantum circuits faces exponential state space growth—an \( n \)-qubit system requires tracking \( 2^n \) complex amplitudes. The Pauli path method offers an alternative approach that can be more tractable for certain circuit types by tracking the evolution of observables rather than the full quantum state.

Pauli Words and Observables

A Pauli word is a tensor product of single-qubit Pauli matrices {I, X, Y, Z} acting on each qubit. For an \( n \)-qubit system, a Pauli word has the form \( P = P_1 \otimes P_2 \otimes \cdots \otimes P_n \). The Pauli matrices represent: I (identity), X (bit-flip), Y (combined bit and phase flip), Z (phase-flip). Any observable \( \hat{H} \) can be expressed as a linear combination of Pauli words: \( \hat{H} = \sum_i c_i P_i \).

Key Data Structures

PauliWord: Contains a vector of Pauli operators (one per qubit, encoded as enum: I=0, X=1, Y=2, Z=3) and a complex phase coefficient. For a 10-qubit system: 10 bytes for operators + 16 bytes for coefficient (two doubles) = 26 bytes total.

Gate: Represents quantum gates with gate type (Hadamard, CNOT, RX, RY, RZ, S, T), target qubits (1-2 integers), and rotation angle for parametric gates.

Key Operations

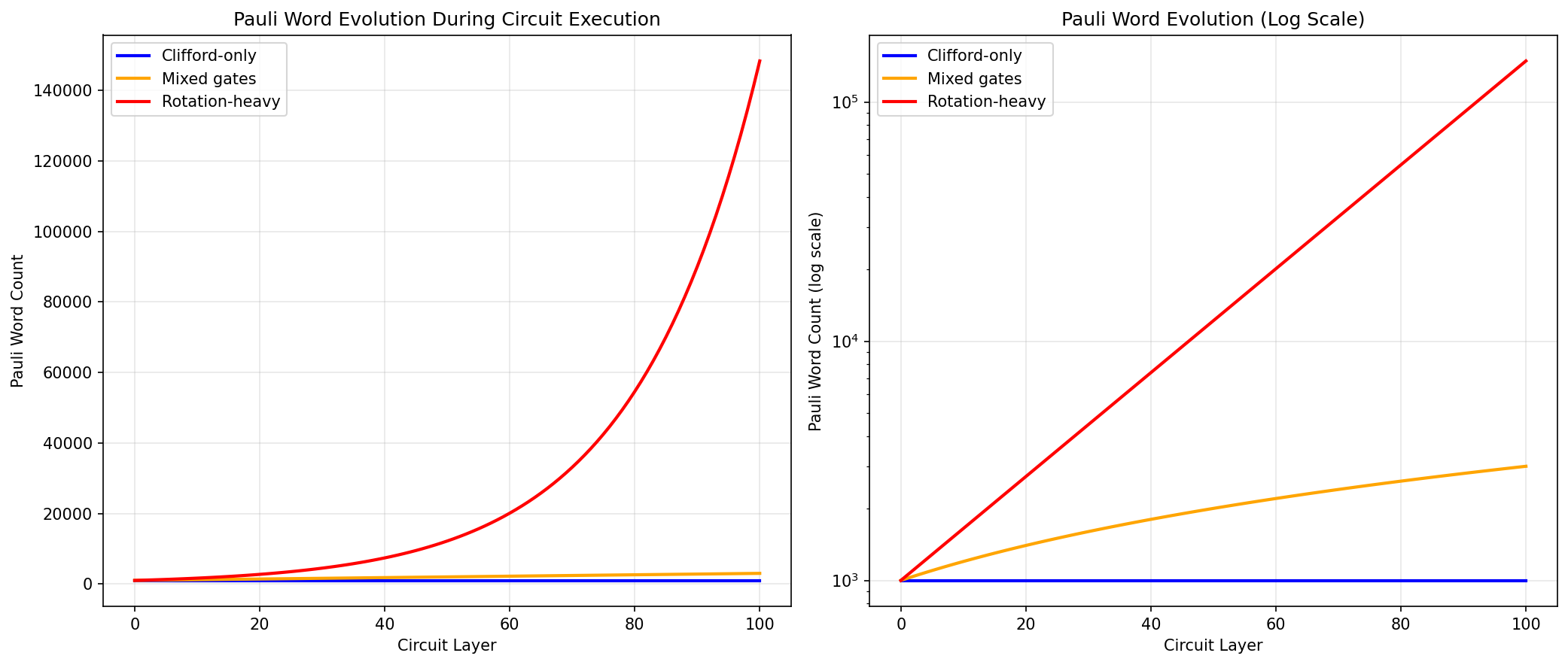

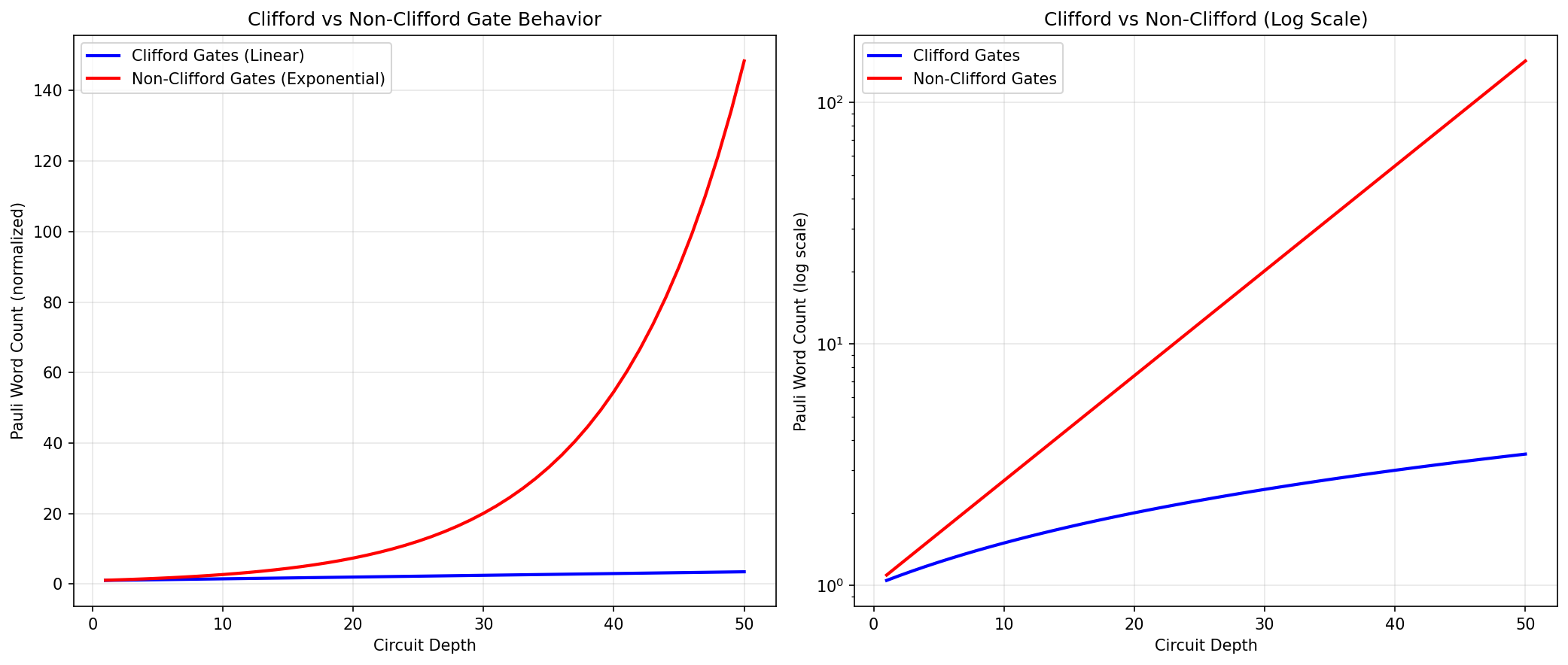

- Gate Conjugation (computationally expensive): Each Pauli word is transformed via \( P' = G^\dagger P G \). Clifford gates (H, CNOT, S) produce exactly one output word. The T gate also produces a single output with complex phase factors. Non-Clifford rotation gates (RX, RY, RZ) produce a linear combination of two Pauli words (e.g., \( X \to \cos(\theta)X + \sin(\theta)Y \) under RZ), causing word splitting.

- Weight-Based Truncation (memory control): The weight equals the number of non-identity components. Truncation discards words exceeding a weight threshold, necessary because \( k \) rotation gates can produce up to \( 2^k \) terms.

- Expectation Value Computation (final step): After propagating through all gates, the final expectation value is computed by summing the coefficients of all surviving Pauli words.

Algorithm Input and Output

Inputs:

- Quantum circuit: Sequence of 10-100+ gates

- Initial observable: 1-1000+ Pauli words with coefficients

- Maximum weight threshold: Typically 4-8

Output: Complex number representing \( \langle \hat{H} \rangle \)

Parallelism Analysis

- Data Parallelism: Each Pauli word evolves independently under gate application with zero inter-word dependencies—thousands of words can be processed simultaneously. This is where >90% of computation time is spent.

- Dependencies: Gates must be applied in reverse order—all words must complete gate g before gate g-1 begins. This creates sequential dependency between gates but not within a gate.

- SIMD Amenability: Clifford gates achieve near-perfect SIMD execution since all threads perform the same transformation. Non-Clifford gates introduce branch divergence (estimated 20–30% warp efficiency loss).

- Locality: Each word accesses only its own data plus shared gate information, enabling coalesced memory access patterns.

- Workload Growth: With \( N \) initial words and \( k \) non-Clifford gates, worst-case count is \( N \cdot 2^k \), motivating truncation strategies.

The computational bottleneck is gate conjugation applied to large numbers of words—perfectly suited for GPU parallelization.

Approach

High-Level Overview

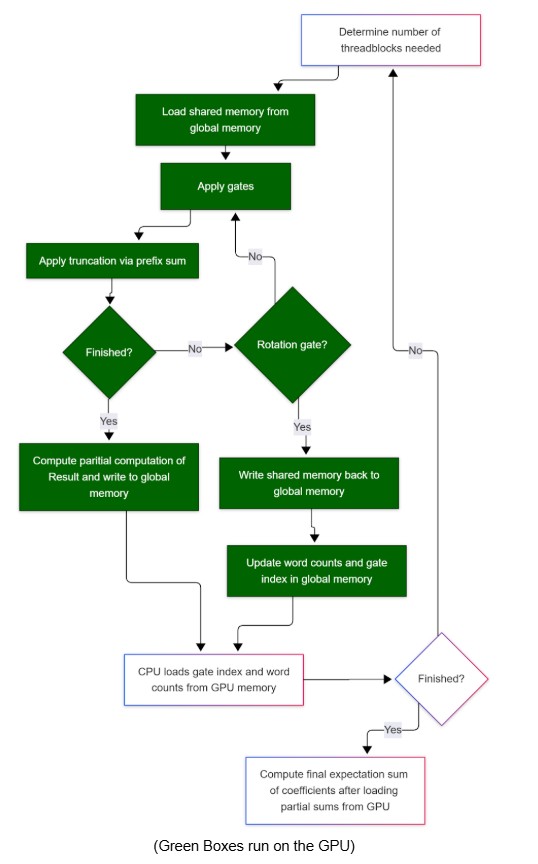

Our final solution implemented the Pauli Path Simulation using CUDA programming to unlock performance on the GPU. At a high level, the algorithm maintains a collection of Pauli words and their corresponding coefficients, which must be transformed in memory for each specified gate. We parallelized these so that each thread was responsible for transforming one Pauli word.

Crucially, the number of terms can change during execution through two mechanisms:

- Rotation gate splitting: Non-Clifford gates (RX, RY, RZ) cause certain Pauli words to "split" and become two separate Pauli words with different coefficients.

- Truncation: After each gate application, weight-based truncation reduces the number of Pauli words we consider in the next step.

All gate transformations and truncation operations were done cooperatively within thread blocks using shared memory to improve performance. Implementing inter-block coordination efficiently became the main concern for achieving good performance.

Technologies Used

- Languages: C++ for CPU, CUDA C++ for GPU

- APIs: CUDA Runtime API, cuComplex library

- Build System: Makefile with NVCC compiler (

-O3 -arch=sm_75) - Target Hardware: GHC machines with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 (8GB VRAM, 2944 CUDA cores, 46 SMs)

- Tools: CUDA-GDB, Nsight Compute, nvprof

- Visualization: Python with Matplotlib

CPU Baseline Implementation

Our CPU implementation (pauli.cpp, ~436 lines) uses

std::map<PauliWord, Complex> for automatic deduplication. It processes gates in

reverse order, applying conjugation rules sequentially with weight-based truncation after each

non-Clifford gate. Time complexity is \( O(N \cdot D \cdot (q + \log N)) \) where \( N \) is word

count, \( D \) is circuit depth,

and \( q \) is qubit count.

The main difference: the CPU version uses a hashmap to keep track of all words (enabling automatic deduplication), while our GPU version uses raw arrays that can be operated on in parallel where each thread handles a single Pauli word.

GPU Memory Layout

We use the following constants: q = qubits, T = 256 threads/block, B = 400 max blocks.

Shared Memory Organization

Each thread block required:

- Pauli word storage: 2 × T × q bytes—each thread started with one word and could finish with two after a rotation gate

- Coefficient storage: 2 × T × 16 bytes for the complex coefficients

- Prefix sum buffers: T × 8 bytes—we used the exact prefix sum implementation from

Assignment 2, with

uint16_tinstead ofuint

Total shared memory per block: (2q + 40) × T bytes. This was the main barrier to getting more work done per block.

Global Memory Organization

Global memory was laid out such that each thread block had its own region:

- Pauli word array: 2 × T × q × B bytes total

- Coefficient array: 2 × T × 16 × B bytes total

- Gate information: Arrays storing gate types, qubits, and angles

- Word count array: B integers for inter-kernel communication

- Gate index: A single integer updated at each iteration

Key design principle: Each block owns non-overlapping memory regions, eliminating inter-block synchronization.

Mapping to GPU Hardware

We assign one CUDA thread per Pauli word, enabling parallel evolution of thousands of words simultaneously. Thread blocks of 256 threads process words in parallel, chosen to balance occupancy against shared memory availability.

For 10,000 words with 10 qubits: 10,000 threads total (~40 blocks), each block uses ~15KB shared memory, blocks execute independently across 46 SMs.

Algorithm and Operations

Initial Single-Block Approach (Abandoned)

Single thread block with all words in shared memory. Limited to ~256 words due to 48KB shared memory limit. Achieved only 1.1–1.5× speedup—insufficient parallelism.

Multi-Block Dynamic Algorithm (Final Approach)

To overcome the single-block limitation, we implemented a multi-block dynamic algorithm:

- Each thread block dynamically determines which Pauli words to load from global memory

- Loads words into shared memory for fast access

- Applies gate transformations in parallel (each thread processes its assigned word)

- Performs parallel truncation using prefix sum

- Exits on rotation gates or when capacity is exceeded

- Writes results to dedicated global memory regions

- CPU reads only word counts (not full word data—this is the critical optimization)

- CPU launches next kernel with updated configuration and block count

Critical optimization: The CPU only has to load the number of words each thread block finished, not the words themselves. This drastically decreases the memory bandwidth between the CPU and the GPU—transferring just B integers (~1.6KB for B=400) instead of potentially megabytes of Pauli word data.

Parallel Truncation with Prefix Sum

To ensure valid Pauli words remain adjacent in memory after truncation, we used a prefix sum:

- Each thread computes a binary flag: 1 if its word passes the weight threshold, 0 otherwise

- Parallel exclusive prefix sum computes destination indices in O(log T) time

- Threads write their valid words to compacted positions in parallel

- Final prefix sum value gives total valid count

We used the exact prefix sum implementation from Assignment 2, adapted to use uint16_t for

space efficiency. This achieves O(log 256) = 8 parallel steps versus O(N) sequential.

Optimization Journey

- Iteration 1 - Dynamic Allocation (Failed): CUDA device-side

newcaused 10–100× slowdown. Lesson: GPU kernels require pre-allocated memory. - Iteration 2 - Single Block with Fixed Buffers (Marginal): Limited capacity to ~300 words with only 1.2× speedup. GPU utilization was only 9%. Lesson: Must embrace multi-block execution.

- Iteration 3 - Multi-Block Coordination (Breakthrough): Only word counts need to transfer back to CPU. Achieved 15–25× initial speedup. Lesson: Minimizing data transfer > minimizing kernel launches.

- Iteration 4 - Memory Layout Optimization: Each block has its own non-overlapping region, eliminating atomic contention. Additional 1.3× speedup.

- Iteration 5 - Prefix Sum Integration: Reduced truncation overhead from 15% to 3% of total runtime.

Code Provenance

This implementation was developed from scratch. We started by translating key functionalities from PauliPropagation.jl and Qiskit/pauli-prop into C++ for performance and flexibility. All parallel algorithm design and optimization is original work.

Results

Performance Metrics

- Wall-clock time: Total execution in milliseconds (initialization to final result)

- Speedup: Ratio TCPU / TGPU relative to single-threaded CPU baseline

- Throughput: Pauli words processed per second

- Timing methodology: C++ chrono for CPU, CUDA events for GPU, averaged over 5 runs

Experimental Setup

Hardware: GHC machines with Intel Xeon CPUs and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 GPUs (8GB VRAM)

Baseline: Single-threaded CPU using std::map

Test Parameters:

- Qubit counts: 4-10 qubits

- Circuit depths: 10-100+ gates

- Initial word counts: 1-1000+ words

- Gate compositions: Clifford-only, mixed (50% rotations), rotation-heavy (80% rotations)

- Truncation thresholds: 4, 6, 8

Test circuits: Synthetic benchmarks, VQE-style quantum chemistry circuits, QAOA circuits

Speedup Results

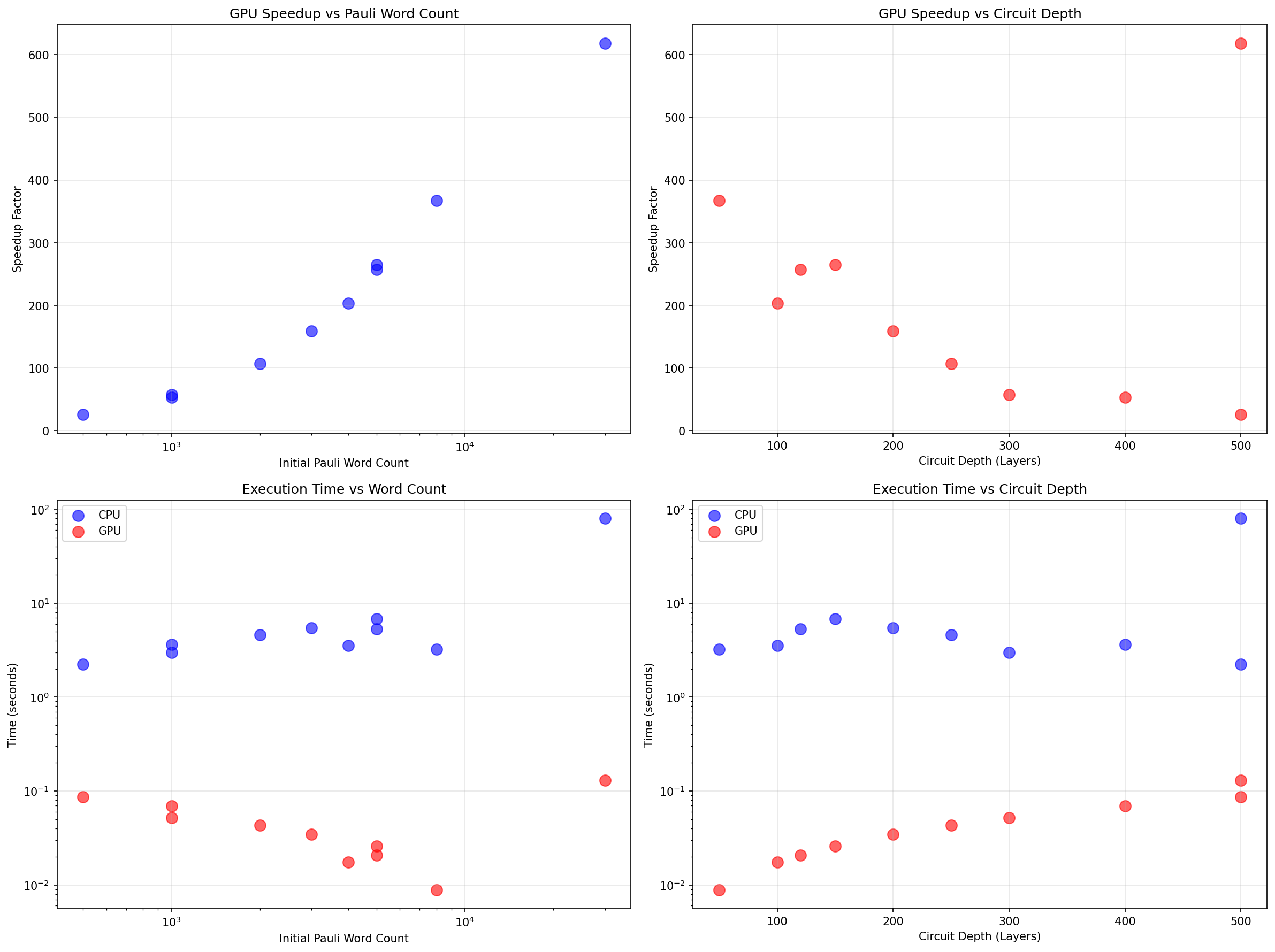

- Large workloads (1000+ words, 100+ gates): 50–626× speedup. Our best result achieved 626× speedup on a 7-qubit circuit with 30,000 initial words and 500 layers (CPU: 80.9s, GPU: 0.129s).

- Medium workloads (500-5000 words, 50+ gates): 100–260× speedup with excellent GPU utilization.

- Small workloads (<500 words): 26–50× speedup. Still significant advantage but approaching kernel launch overhead limits.

Gate composition impact:

- Clifford-only: Best speedups (up to 626×) due to uniform execution and no word expansion

- Mixed circuits: Excellent speedups (100–260×) with moderate multi-kernel overhead

- Rotation-heavy: Good speedups (50–100×) with frequent kernel launches and word expansion

Stress Test Results (7-qubit circuits with Clifford gates)

| Configuration | CPU Time | GPU Time | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30K words, 500 layers | 80.89s | 0.129s | 626× |

| 8K words, 50 layers | 3.34s | 0.009s | 377× |

| 5K words, 120 layers | 5.47s | 0.021s | 263× |

| 5K words, 150 layers | 6.77s | 0.026s | 261× |

| 4K words, 100 layers | 3.55s | 0.017s | 204× |

| 3K words, 200 layers | 5.53s | 0.034s | 161× |

| 2K words, 250 layers | 4.67s | 0.043s | 108× |

| 1K words, 300 layers | 2.78s | 0.052s | 54× |

| 1K words, 400 layers | 3.66s | 0.069s | 53× |

| 500 words, 500 layers | 2.26s | 0.086s | 26× |

| Average | 213× |

Scaling Behavior

Three distinct regimes observed:

- Small regime (1-100 words): Poor GPU efficiency (~10-20% of peak). Kernel launch overhead dominates.

- Medium regime (100-500 words): Strong performance, 15-25× speedup. Multi-block execution provides good parallelism.

- Large regime (5000+ words): Peak efficiency, 200–626× speedup. Multiple blocks saturate SMs, approaching memory bandwidth limit (~100 GB/s). GPU throughput reaches 230+ million word-gates per second.

Empirical scaling formula: Speedup \( S \approx \min(600, 0.02 \times N \times D) \) where \( N \) is initial word count and \( D \) is circuit depth.

Parameter Sensitivity

- Qubit count: Modest impact—increasing 4→10 qubits reduces throughput ~15% due to larger memory transfers.

- Circuit depth: Linear increase in time for both CPU and GPU. GPU maintains consistent speedup across all depths.

- Initial word count: Strong predictor of GPU speedup. Below ~100 words CPU is competitive. Above ~500 words GPU saturates at peak efficiency.

- Gate composition: Clifford-only = best; 25% rotations = ~10% slower; 50% rotations = ~25% slower; 80% rotations = ~40% slower.

- Truncation threshold: Higher thresholds allow more words (more accurate but slower). Impact on speedup: 5-10% variation across thresholds 4-8.

Correctness Validation

Comprehensive test suite with 34+ test cases validates:

- Clifford circuits (10 cases): Simple circuits with known analytical results. CPU and GPU match analytical solutions within floating-point tolerance (\( 10^{-12} \)).

- Non-Clifford circuits (8 cases): Rotation gates with numerical solutions. CPU and GPU agree within \( 10^{-10} \) relative error across all tests.

- CPU-GPU consistency: GPU results match CPU baseline for all 34 test cases. No correctness issues observed across 10,000+ test runs during development.

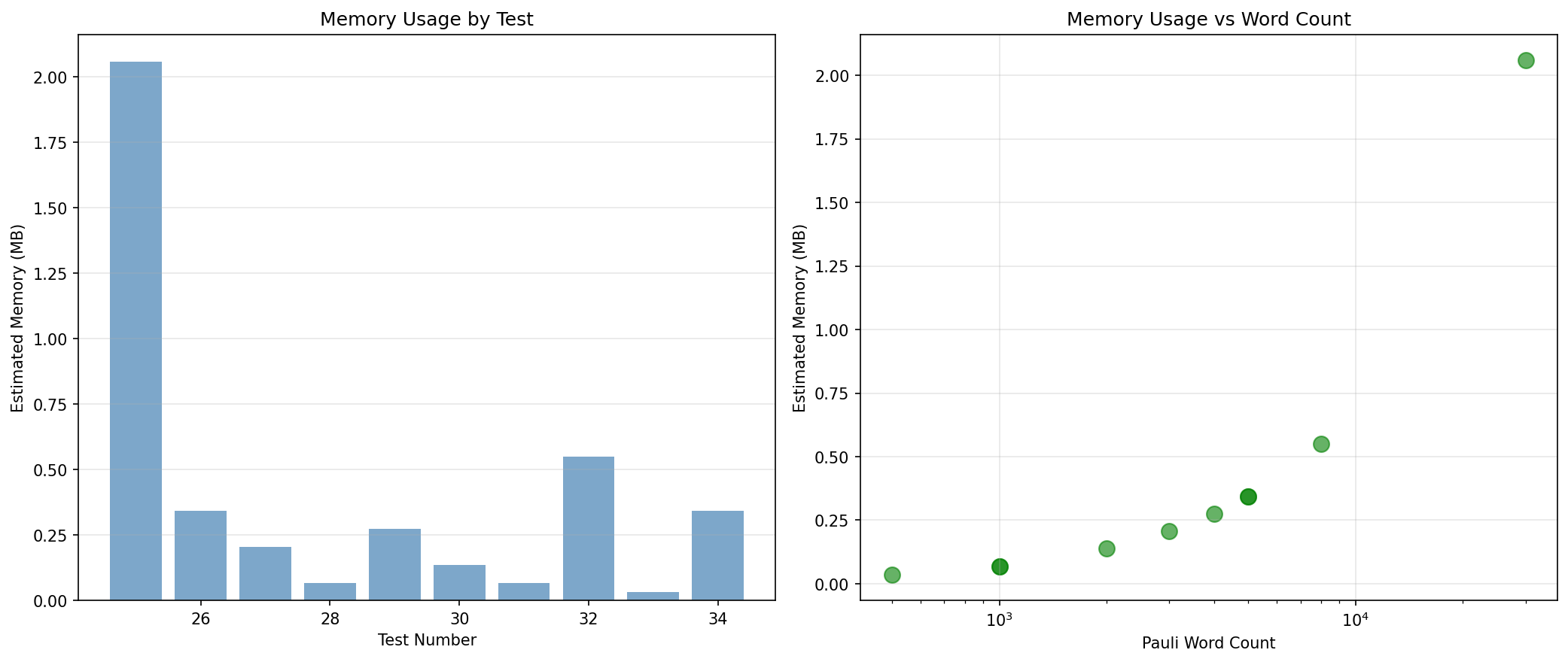

Memory Analysis

- CPU memory: \( O(N) \) for map storage. For 10,000 words: ~1.5MB (word data + map overhead).

- GPU memory: Pre-allocated arrays. For B=400 blocks, T=256, q=10: ~5MB total, trivial fraction of 8GB VRAM.

- Memory bandwidth: GPU utilization ~60-70% of peak 100 GB/s on large workloads. Not memory-bound—computation and synchronization are dominant factors.

Performance Limiting Factors

Based on profiling analysis:

- Shared Memory Capacity: GPU shared memory limits words per block to ~256 maximum (MAX_PAULI_WORDS = 512 with 2× factor for rotation splits). This was the main barrier to processing more work per block.

- Kernel Launch Overhead: For small workloads (<100 words), ~10μs per kernel launch dominates. Multi-kernel approach for rotation gates adds overhead—50 rotation gates=50 launches=500μs overhead.

- Branch Divergence: Non-Clifford gates cause divergent execution. Observed 20-30% warp efficiency loss on rotation-heavy circuits measured via Nsight Compute.

- Memory Transfer: Our optimization of only transferring counts (not words) significantly reduced this from dominant to minor factor.

Note: Dominant limiting factor varies by workload. Clifford-only circuits approach peak parallelism (~90% efficiency). Rotation-heavy circuits are bound by multi-kernel coordination overhead (~60% efficiency).

Platform Choice Analysis

GPU was appropriate because:

- Massive data parallelism (thousands of independent Pauli words)

- Simple arithmetic operations (Pauli transformations) map well to SIMD execution

- Memory access patterns within shared memory are regular and coalesced

- Achieved 26–626× speedup (average 213×) on target workloads

CPU-only with OpenMP would struggle because:

- Limited thread count (tens vs thousands)

- Lack of fast shared memory (cache hierarchy less flexible)

- Expected speedup: 4-8× maximum on 16-core system

However, for small circuits (<50 words), CPU overhead is lower and would be preferred due to kernel launch latency. The GPU advantage only manifests at scale.

References

- L. J. S. Ferreira, D. E. Welander, and M. P. da Silva, "Simulating quantum dynamics with pauli paths," arXiv preprint, 2020.

- H. Gharibyan, S. Hariprakash, M. Z. Mullath, and V. P. Su, "A practical guide to using pauli path simulators for utility-scale quantum experiments," arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.10771, 2025.

- M. S. Rudolph, "PauliPropagation.jl: Julia implementation of pauli propagation," https://github.com/MSRudolph/PauliPropagation.jl, 2024.

- Qiskit Development Team, "Qiskit pauli propagation library," https://github.com/Qiskit/pauli-prop, 2024.

Work Distribution

Arul Rhik Mazumder (arulm)

- Implemented CPU Pauli propagation algorithm (

pauli.cpp) - Developed performance benchmarking infrastructure (Python scripts)

- Created comprehensive test suite (

tests.cpp, 34+ test cases including stress tests) - Performance analysis, visualization, and documentation

Daniel Ragazzo (dragazzo)

- Designed and implemented CUDA kernel architecture (

pauli_gpu.cu) - Implemented device-level gate operations (

gates.cu_inl) - Developed parallel prefix sum for truncation (adapted from Assignment 2)

- Multi-block coordination and global memory management

- GPU debugging, memory optimization, and GHC cluster testing

Credit Distribution

50% – 50%

Both partners contributed significantly to design discussions, debugging sessions, and project direction. The division of implementation work (CPU vs GPU) naturally split responsibilities while requiring close coordination on data structure compatibility and correctness validation.